Introduction to R 1#

General information#

Main objective#

In this lecture we will introduce R, a programming language for data analysis and statistics.

Learning objectives#

Students can use R Studio to write scripts and execute code

Students can recognise and use variables, types and functions

Students can import and export data

Students understand names, indexing and can slice data

Resources#

This section requires the use of the R Workbench.

R Workbench#

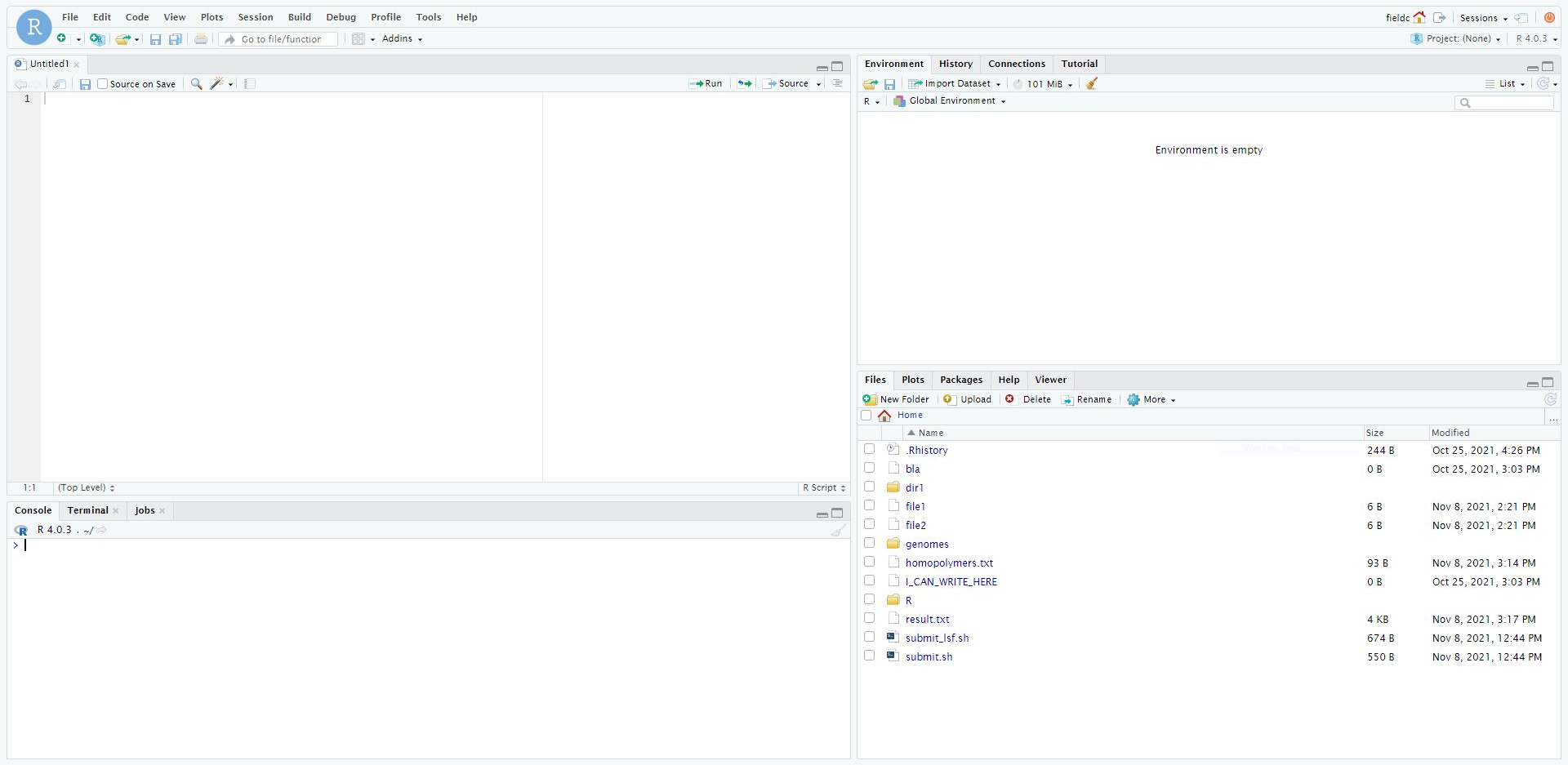

R Workbench is an integrated development environment (IDE) for R. This means that it provides an interface to help you write, run and debug code. It is an extended, web-based version of R Studio, which you might like to use on your own computer for working in R.

The bottom left panel is the R console. Here you can type in commands and have them immediately evaluated.

The top right panel shows you the current variables in your environment. By default you are shown the variable names and a short preview of their contents, but you can get more information by changing the view type from List to Grid. Another tab here shows you your command history.

The top left panel is where you can view and edit script files, and where can you view 2D variables such as matrices and data frames (more on those later). Initially this panel will not appear, but you can bring it up by going to the menu, File -> New File -> R Script.

The bottom right panel shows a file browser. If you are working on the web version, this will show your Unix home directory by default. Other tabs show plots that you create, additional functions, known as packages, you have installed, and help files for various functions.

Useful commands#

When you want to run the entire script you are looking at, you can press Control+Shift+Enter.

When you just want to run a single line in the script, or the lines you have highlighted, you can press Control+Enter.

If you want to interrupt a running command or script, you can press Escape in the console window.

If something goes really wrong, you can select Interrupt R or Restart R from the Session menu.

Other tips#

Use the R console to try things out, and when you’re happy that you have written a command correctly you can copy and paste it into your script

The R console works very much like the Unix terminal:

You can use the arrow keys to scroll back through previously run commands

You can use tab to auto-complete commands and variables - a handy menu comes up with options if there is ambiguity

Unlike the Unix terminal, in R Studio you can copy and paste as you would do normally in other programs

In the script window there are line numbers to make it easier to find errors

Calculation and variables#

R as a calculator#

Using R at its most basic, it is a calculator. You can enter a calculation into the console and immediately evaluate the result.

# R is a calculator

1 + 2

3 * 4

Variables#

A core concept in programming, a variable is essentially a named piece of data. That is, when you refer to the variable by its name within the program, you are actually referring to the data stored under that name.

To assign data to a variable in R, use the following syntax:

# Assignment

x <- 2

y <- 3.5

After you have assigned data to variables, you can then use the variables to perform calculations:

# R is a clever calculator

x + 2

x * y

z <- x + x + x

If you need to see the value of a variable in the command line, you can just type its name:

# What is x?

x

Note that variable names are case sensitive, and cannot start with a number.

Exercises

Experiment for yourself with the R command line to do some simple calculations

Assign some different numbers to the variables x and y and check if calculations with them work as you expect

Try to do a calculation with a variable you haven’t assigned any data to, a for instance

Set x to 1, then check what happens when you run the calculation x <- x + 1, what value is x afterwards?

Be aware that R has special values for certain calculations - try dividing by 0 for instance.

Types#

In R, and many other languages, variables also have a type, which defines the sort of data they store. R is actually a bit more complicated because it has modes and classes:

A mode is most like a type in other languages, and determines the type of data stored, such as ‘numeric’ or ‘character’.

A class is a container that describes how the data is arranged and tells functions how to work with the data.

Some modes you might encounter:

numeric - numbers, including integers and floating points numbers

character - strings

logical - TRUE or FALSE

list - a special mode for containing multiple items of any, possibly different, mode(s), whose mode becomes ‘list’

Some classes you might encounter:

vector - a one-dimensional set of items of the same mode

matrix - a multidimensional set of items of the same mode

data.frame - a two-dimensional table with columns of different modes

formula - a declaration of how variables are related to each other, for fitting models

factor - a categorical variable

The reason that it is sometimes important to know what mode and class your variable has, is that functions behave differently according to the data they are given. It’s easy to accidentally transform your variable into an unexpected format and then get an unexpected result from the functions you use in your program.

Mode detection#

To a certain extent, R will auto-detect what mode a variable should have based on the data. There are convenient functions to check a variable’s mode when you need to.

# Auto-detection of variable mode

x <- 1

y <- "word"

mode(x)

mode(y)

# What about if we make a mistake

x <- "1"

is.numeric(x)

Vectors#

If we want to create a variable that contains multiple pieces of data, we must make a declaration when we assign data to the variable.

# Creating a vector

x <- c(1, 2, 3)

x

# Lazy sequences

x <- 1:3

x

# Creating a vector with variables

x <- 1

y <- 2

z <- c(x, y, 3)

z

Exercises

Create a vector containing the numbers 1 to 10

What happens if you add 1 to this variable?

What happens if you multiple the variable by 2?

What happens if you add the variable to itself?

Now create two vectors of the same length containing different numbers, say 1 to 3 and 4 to 6.

What happens when you add or multiply these together?

What happens if you add or multiply two vectors of different lengths?

Lists and data frames#

Lists#

Vectors and matrices have the limitation that they must contain data all in the same mode, i.e.: all numbers or all characters. Lists circumvent this limitation, acting as containers for absolutely any type of data.

# Declare an empty list

l <- list()

# Declare a list with items

l <- list("a", 1, "b", 2:4)

l

# Declare a list with named items

l <- list(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34))

l

Data frames#

In that last example, it would be ideal if we could link the names with the scores, and maybe further data. We can store tabular data in R in a data frame, which is really a special kind of list.

# Declare a data.frame

df <- data.frame(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34))

df

Looking at the df, you can see that the data is neatly arranged in named columns. You can also change the format of a variable between list and data frame quite easily.

# Change between list and data.frame

l <- list(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34))

df_from_l <- as.data.frame(l)

df <- data.frame(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34))

l_from_df <- as.list(df)

If you then look at l_from_df, the way the list is shown includes the line ‘Levels: Anna Ben Chris’. Levels are the possible choices for a categorical factor, which is a variable mode in R for storing that sort of data. Data frames will almost always convert text into a factor, which will cause that data to behave differently than a character variable. This can be avoided:

# No factors please

df <- data.frame(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34), stringsAsFactors=F)

as.list(df)

Exercises

Create a simple list containing some numbers - not vectors of numbers

What happens if you try to do arithmetic with the list?

Now create a data frame with three columns, a name and two numeric values per name, such as coordinates.

What happens if you try to do arithmetic with the data frame?

Importing and exporting data#

Importing data#

R has a host of functions for importing data of different types. I generally recommend that if you have a data table from Excel, for instance, you save the file as tab-delimited text for import into R. The most versatile import function is read.table.

# Import a data table

genes <- read.table("/nfs/course/rfiles/ecoli_genes.txt")

We can now see what the table looks like using the Environment tab in the top-right - but something went wrong and the column headings are in the first row. We can fix this pretty easily.

# Import the table again

genes <- read.table("ecoli_genes.txt",header=TRUE)

There are a few other useful arguments to help import tables of various formats:

sep - determines the field separator (between columns), i.e.: sep=”,”

quote - determines the quote mark (items in quote marks are considered to be the same field), i.e.: quote=”"”

row.names - determines which column contains the row names, if there are any

comment.char - determines which character, if at the start of a line, indicates the line should be ignored, i.e.: comment.char=”#”

stringsAsFactors - determines whether the table should turn text into factors, which you may want to turn off, i.e.: stringsAsFactors=F

Exporting data#

Conversely, R has functions for exporting data into different formats. You will most likely want to create a file to open in R later, or a .csv file to open in Excel.

# Write a data.frame to an R-friendly format

write.table(df,"Rfriendly_df.txt")

# Write a data.frame to a .csv file

write.csv(df,"df.csv")

Many of the arguments for the read functions also apply to the write functions, so you can decide whether you want to see row or column headings, how the text fields are separated, etc.

Exercises

Download and import the ecoli_genes.txt table for yourself, make sure to get the column headings correct

Write the table out to a new file name using write.table

Now import the table again without any additional arguments to read.table - do you still need to correct the column headings?

Names and Indexing#

Names#

In R, it is not just variables that have names. We have seen that data frames can have column names, and it’s also possible to give them row names. In fact, any element in a vector or list can be given a name, and these names are accesible through a simple function.

# Naming a vector

x <- 1:5

names(x) # NULL

names(x) <- c("A","B","C","D","E")

names(x)

x

This is slightly different in a matrix or data.frame, where you can name the rows and columns.

# Naming rows and columns

df <- data.frame(1:3,4:6,7:9)

df

rownames(df)

colnames(df)

rownames(df) <- c("A","B","C")

colnames(df) <- c("X","Y","Z")

df

Indexing#

Sometimes you want to refer to only part of a vector, matrix or data.frame – perhaps a single column or even single item. This is called slicing and requires an understanding of how R indexes the elements in objects.

For a vector, you can either reference an item by its position or name.

# Slicing a vector

x <- c("Chris","Field","Bioinformatician")

names(x) <- c("Name","Surname","Job")

x[1]

x["Name"]

For a matrix or data.frame, the same methods work for indexing the row or column of the object, or both. The convention is that first you give the row, then the column, separated by a comma, and if one is left blank it implies you want ‘all’ rows or columns. For this example we are going to load up a pre-made set of data that comes with R.

# Slicing a data.frame

data(swiss)

swiss[1,]

swiss[,1]

swiss[1,1]

swiss["Gruyere",]

swiss[,"Fertility"]

Finally there are two additional ways to access items in a list, or columns (only) of a data frame.

# Accessing a list item

l <- list(names=c("Anna", "Ben", "Chris"), scores=c(23, 31, 34))

l$names

l[[1]]

l[["names"]]

# The difference between single and double brackets for a list

l[1] # Produces a list of one item

l[1:2] # Produces a list of two items

l[[1]] # Produces a vector

l[[1:2]] # Produces a single item, the second entry in the first item in the list

# Accessing a column of a data frame

swiss$Fertility

swiss[[1]]

swiss[["Fertility"]]

You can also slice multiple items by giving a vector of numbers or names. Remember that R automatically translates the code n:m into a range of integers from n to m.

# Slicing a range

x[1:2]

swiss[1:3,]

swiss[4:5,1:3]

swiss[c("Aigle","Vevey"),c("Fertility","Catholic")]

Exercises

Load the pre-made data set swiss

Look at the row and column names, then try to rename the columns

What happens if you give fewer names than there are columns?

Create a vector containing the numbers 1 to 10 and then create a vector containing the first ten square numbers

Slice the vector to check the value of the 7th square number

Returning to the swiss data set, extract the data for just Sion

Now extract only the Catholic data for the first ten places, and for just Sion

Finally use vectors to find the data on Examination and Education for Neuchatel and Sierre

Logical slicing#

We have seen that we can give R a vector of numbers or names and it will slice out the corresponding data from a vector or data frame. We can actually go further than that and use a vector of logical values, TRUE or FALSE to determine which elements we want to slice out. Furthermore, we can write the vector as a variable ahead of time if we like.

# Slice using premade vectors

places <- c("Neuchatel","Sierre")

cols_of_interest <- c("Examination","Education")

data(swiss)

swiss[places,cols_of_interest]

# Slice using a logical

cols_of_interest <- c(FALSE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE)

swiss[places,cols_of_interest]

Now the really clever bit is that we can generate a vector of logical values using the data itself, with any of the comparison functions such as >, <, ==.

# Logical slicing

isCatholic <- swiss$Catholic > 50

swiss[isCatholic,]

# Logical slicing without saving the vector ahead of time

swiss[swiss$Fertility < 50,]

Exercises

Reload the swiss data set, in case you have edited it

Create a vector with the column names in alphabetical order and use it to ‘slice’ the table (we are really just rearranging!)

Slice the table to see just the places with an Agriculture score less than 50

Now, making sure to save the results into new variables, split the table into two based on whether a place has more or less than 50 in Catholic

In each table, look at the Catholic column data only, what do you notice about it?

Homework

Load a dataset with information on US states with the command data(state)

This creates several variables - you can see information on the data with the command ?state

Calculate the total income for each state with the data in state.x77

Use the state.region variable to slice the data frame state.x77 - for each region calculate the total income of all states within it

As a sneak preview of the next part, you will find the sum() function useful!

Do the same using state.division

Write all of your commands into a script and save it in your home directory as homework.r