Predicting protein folding and the impact of mutations¶

General information¶

Main objective¶

In this lecture we will learn about one of the longest running challenges in biology and bioinformatics - to understand and predict how a protein sequence folds into a specific 3D structure. We will also learn about different computational methods to predict the impact of protein mutations with a focus on the use of protein structure information.

Learning objectives¶

The students understand the problem of protein structure prediction from sequence and some of the different computational approaches that have been used to tackle this problem

The students understand how changes in protein sequence can cause an impact on protein function and how this can be predicted from the 3D structure of a protein

Students gain proficiency in predicting protein structure using AlphaFold2 and predicting the impact of mutations using FoldX

Resources¶

This section requires the use of the R Studio: http://cousteau-rstudio.ethz.ch

We will also use Pymol (please make sure it is installed in your laptop): https://pymol.org/2/

Video¶

This section has a complementary video:

The protein structure prediction problem¶

Even a relatively small protein sequence could, in principle, adopt an astronomically large number of different conformations, given the high number of degrees of freedom in bond angles. Given this high number of possible conformations, it was noted before that it would take a protein more time to reach its folded conformation by random searching than the age of the universe. However, proteins can fold into defined 3D structures in milliseconds and do this robustly and reproducibly. This paradox was first noted by Cyrus Levinthal and it is often called Levinthal’s paradox. It has been clear for a long time that protein folding is not a random search through possible conformations but there must be a series of rules by which the protein folds. For example, there must be local interactions that help guide the formation of secondary structural elements and then further interactions between these secondary structural elements that result in the most stable folded state.

If there are rules of local and higher order interactions that guide a protein sequence to the folded state then these should be possible to capture in a computational model. This has been a great challenge in bioinformatics that has been approached by different methods. One strategy - named homology modeling - involves searching for other known structures with an homologous sequence to the target protein sequence. While homology modeling can be highly accurate it fails for cases with low sequence identity. Another set of approaches has relied on the development of energy functions that can quantitatively score the energy of a given conformation. Efficient search algorithms are then used to search through possible conformations that are scored by the energy functions.

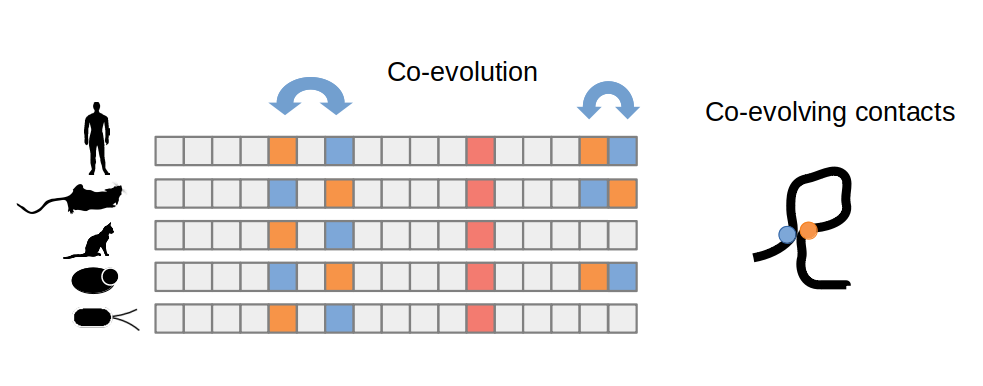

One of the most important developments in reducing the number of possible conformations to search has been the realization that evolutionary information can be highly informative of which residues are close together in the protein structure. Protein residues that are close together in 3D space will often show patterns of correlated mutations across different species. If one residue is mutated, another mutation in an interacting residue may also be preferred and selected for during evolution. As illustrated in the figure below this pattern of coevolution can be used to predict proximal residues.

Another major advance in this problem has been the use of neural network predictors that have been implemented in different tools, the most notorious of which is the Alphafold2 predictor. Neural networks are capable of using very large amounts of data to learn underlying patterns even when we don’t have good theories to explain such patterns.

Every two years since 1994 there has been a competition called CASP (Critical Assessment for protein Structure Prediction), where developers can test their computational methods against several experimentally determined protein structures that are released for the competition. While steady progress has been made over decades of work the last two competitions (2018 and 2020) saw the introduction of the AlphaFold algorithms which have led to predictions that, for the first time, come close to experimentally derived 3D models.

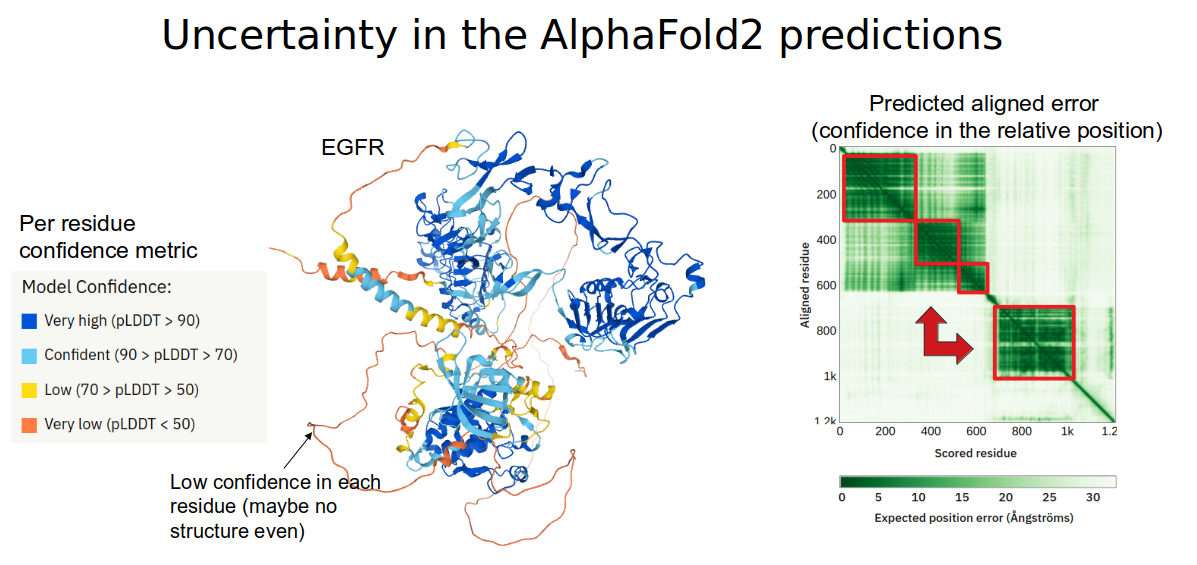

One important point about making use of Alphafold2 predictions is that they come with two confidence metrics (see figure below for an example). There is a per-residue confidence metric called pLDDT which ranges from 0 to 100 and describes the prediction of accuracy for an individual position within the protein sequence. Positions with values above 70 can be considered to be well modeled and those below 50 are considered to be poorly modeled. However, values below 50 also tend to be associated with positions known not to have any structure so these may also be considered to be predicted as disordered or without structure. The second confidence metric is the Predicted Aligned Error which is given in the form of a matrix that describes how confident the model is about the relative position in the space of any two given positions. It is possible that the model is very confident about the structural prediction of two positions but not confident at all about their relative orientation in space.

In the figure above, there is an example of a prediction for the structure of the human EGFR protein. Several regions are predicted to have very high confidence (pLDDT>70, blue colors on the protein structure image). However, the relative orientation of the regions is not predicted to be very accurate as shown by the low scores in predicted aligned error for many pairs of residues in the matrix to the right.

The SwissModel and AlphaFold model repositories¶

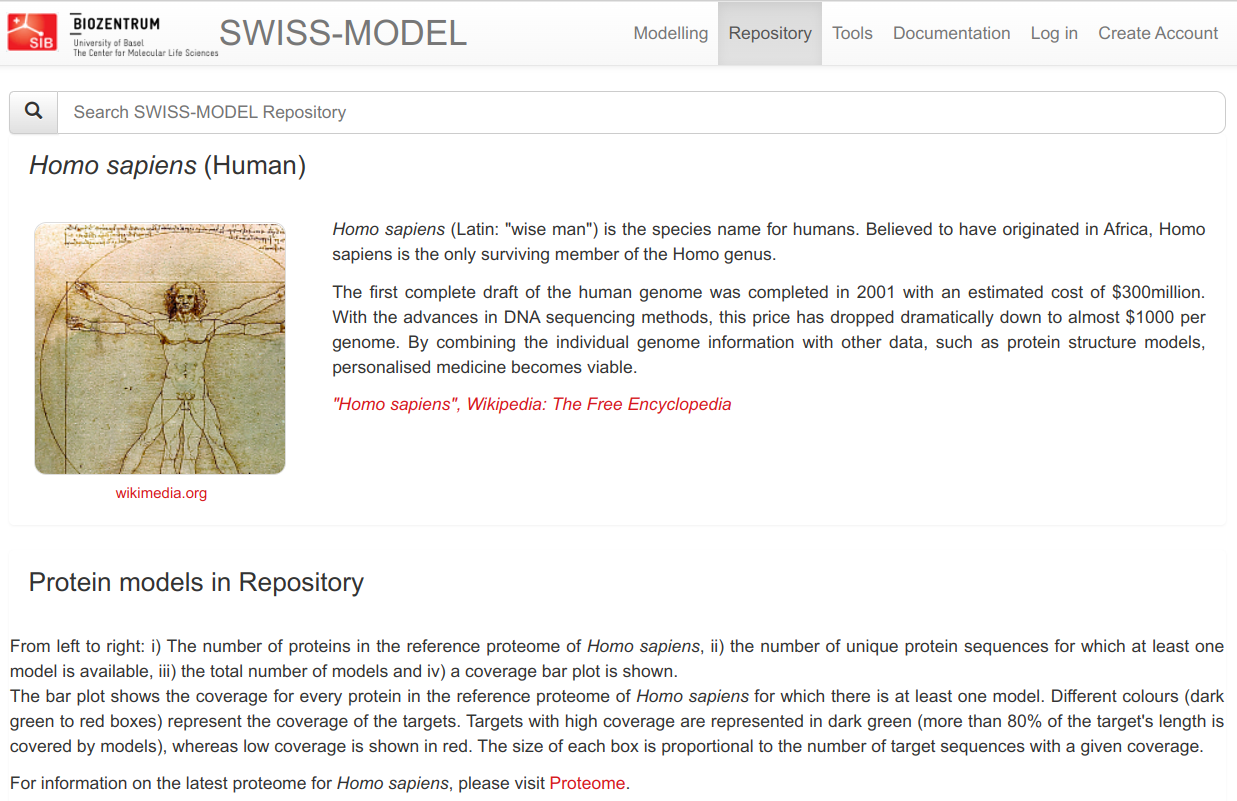

Protein structures have been predicted on a large scale for some species using both homology modeling approaches and using the AlphaFold2 algorithm. A good source of homology models for human proteins and a few other species is the SWISS-MODEL repository. This repository has an up-to-date set of predicted structures based on homology and for human this currently covers approximately 50% of all protein residues. SWISS-MODEL also allows you to build your own homology models based on any sequence of interest.

The AlphaFold database at EBI (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk) is a repository of protein structures predicted using the AlphaFold2 algorithm. It currently holds predicted structures of close to 1 million proteins and it is scheduled to grow to 100 million over the course of the next few years, covering a very large proportion of the non-redundant set of known proteins. It is fairly easy to search through and allows you to download the corresponding files for manipulation.

Predicting protein structures using AlphaFold2¶

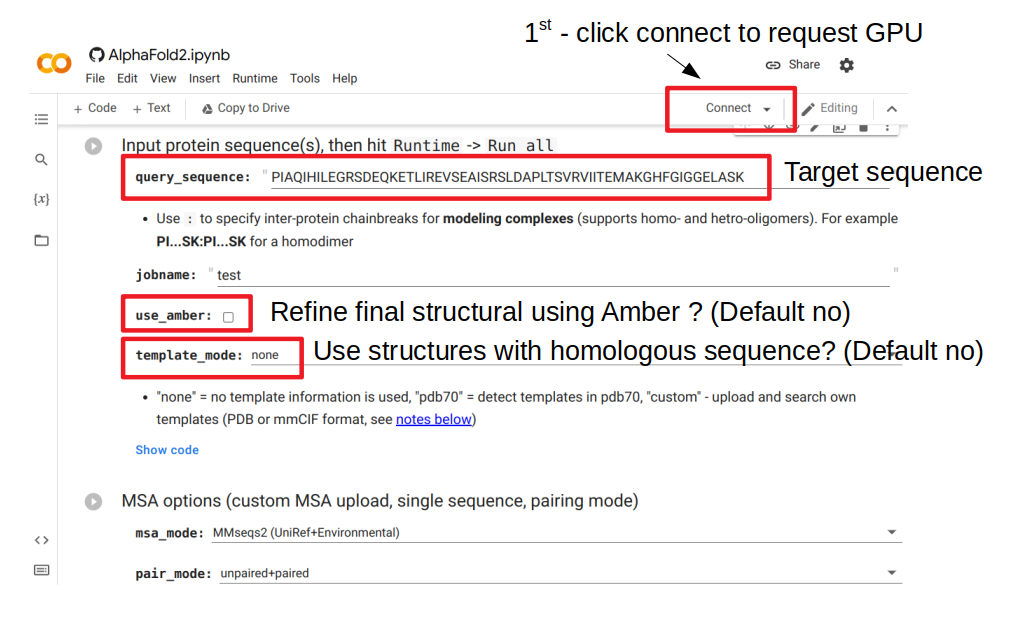

AlphaFold can be easily used to make novel protein structure predictions for your sequence of interest. This can be done via the browser using an easy to use colab notebook called ColabFold.

The figure above shows the important parameters to consider when making a prediction using this web server. The first thing to do is to click connect, which will request a GPU node to serve as resources for this run. The query_sequence element needs to be changed to the target sequence to model. Then the user needs to decide if they want to refine the structure after it is predicted; this will attempt to finetune some of the details to improve bonds and avoid clashes. This additional step is slow and often not very useful. The user can also choose to use or not structures from sequences that are homologous to the target sequence (“template_mode”). By default it is set to “none” which means no use of template. Changing this value to “pdb70” will add a step where homologous structural templates are used to further improve the result.

After all selections were made, the prediction can be generated by going to the menu and selecting Runtime -> Run all. This will take some time that depends on the size of the protein and will generate a predicted structure and some useful plots that relate to the confidence in the prediction.

Predicting the impact of protein mutations¶

Mutations can be introduced in DNA during the normal functioning of any cell. Some of these changes can lead to diseases such as cancer but they are also the source material for selection to act upon during the course of evolution. There are many types of genetic changes such as large deletions or insertions or smaller single nucleotide changes. When these changes occur within protein coding regions they have the potential to change the coding amino-acids and consequently also the structure and function of proteins. Given the importance of such changes, there has been a large number of methods developed to predict when such mutations have an impact on protein function. There have been two major types of predictors, ones that rely primarily on information from sequence evolution and others that rely primarily on protein structure.

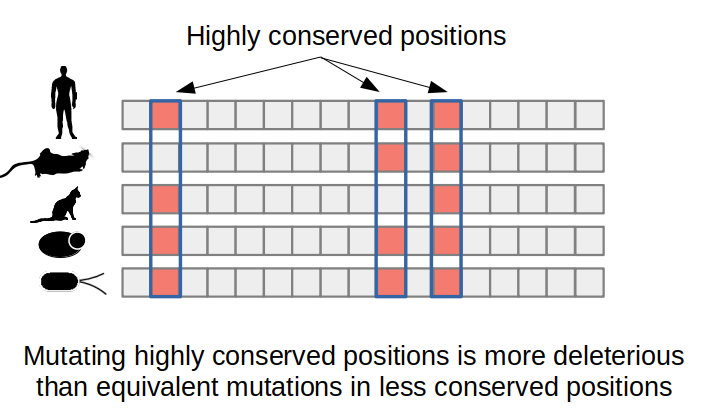

Predicting the impact of a mutation from evolution related information primarily makes use of multiple sequence alignments of the protein of interest together with homologous sequences, usually orthologs (i.e. same protein in different species). Analyzing the resulting alignment can identify which amino-acid changes occur less often in natural sequences and therefore are likely to be deleterious to protein function. For example, enzyme catalytic residues are often extremely conserved and this conservation can be easily detected in a multiple sequence alignment. The SIFT algorithm is an example of a computational method that uses protein sequence conservation to predict the impact of protein mutations.

Structure based prediction of the impact of protein mutations¶

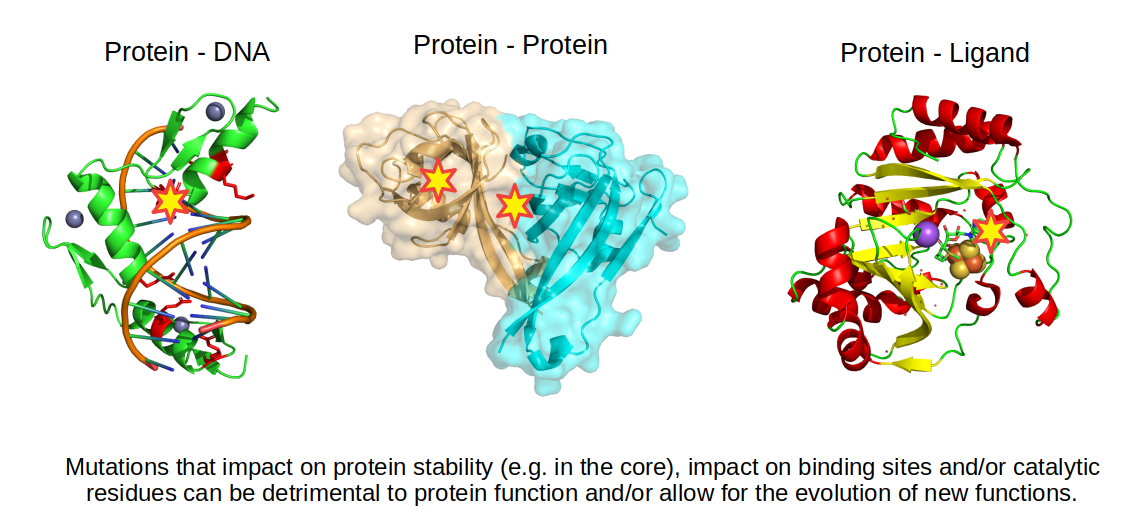

Protein structures are very useful in predicting the impact of a mutation since we can identify changes in amino-acids that could stabilize or destabilize different types of bonds. For example, if a positive residue is making an ionic bond with a negative residue, mutating this negative residue to a positive one will be detrimental to the stability of the structure. Changing residues in the core of the protein to more hydrophilic residues or mutating a small amino-acid to a large amino-acid in the core of the protein may also reduce the stability of the protein. Not all mutations are detrimental, some may change the function of the protein by changing the way the protein interacts with other molecules.

Folding of a protein sequence into a folded state should be thermodynamically stable and the change - or delta - in Gibbs free energy (𝚫G) should be negative when the folded state is more stable than the denatured state. Computationally it is possible to predict this 𝚫G by accounting for all bonds forming within the structure. In addition, the impact of a mutation can then also be predicted and it is often described as the change in 𝚫G or 𝚫𝚫G. When a mutation is destabilizing, 𝚫𝚫G is positive and when it is stabilizing, the 𝚫𝚫G is negative. Most single point mutations in proteins tend not to have an impact on protein stability with 𝚫𝚫G close to 0. Deleterious mutations are strongly enriched when the 𝚫𝚫G >= 2 kcal/mol.

Structural information can also be used to predict the impact of mutations on binding to other molecules. The simplest approach is to find interface residues and overlap with the mutated residues. If the mutation changes dramatically the property of the amino-acid then it may also impact the binding. More sophisticated approaches attempt to quantify the change in binding affinity based on the properties of the bonds formed between the molecules.

Prediction of the impact of protein mutations using FoldX¶

The FoldX algorithm (https://foldxsuite.crg.eu) can be used to estimate both the stability of a protein (𝚫G) and its change upon mutation (𝚫𝚫G). It relies on statistical energy functions that have information on different properties of bonds, clashes, entropy, etc. It has a manual with information on the different capabilities and functions. To test FoldX we will be using the same structure of the human protein kinase A (5J5X). As FoldX generates several files during the process it will be best to create a dedicated directory to use it. In the terminal we can make a new directory, navigate to it and download the PDB file. To run FoldX you need to access the terminal, either by using SSH or by going to the terminal window in Rstudio. In the terminal we can make a new directory, navigate to it and download the PDB file. To use FoldX we will first have to import the FoldX module.

mkdir foldxtest

cd foldxtest

wget http://ftp.rcsb.org/download/5J5X.pdb

ml FoldX

FoldX requires a file “rotabase.txt” in the local directory where it is being used. This can be copied from a location within the same server:

cp /nfs/nas22/fs2202/biol_micro_teaching/software/easybuild/software/FoldX/4.0/bin/rotabase.txt ./

In order to first use FoldX to estimate the impact of mutation we must first attempt to repair it to the most stable state as predicted by FoldX. Running the RepairPDB command, will ask FoldX to change the conformation of the side-chains to avoid clashes and optimize overall the stability of the structure. FoldX does change the backbone of the structure, only moving the side-chains. This repair can take 5-10 minutes to conclude depending on the size of the protein.

foldx --command=RepairPDB --pdb=5J5X.pdb

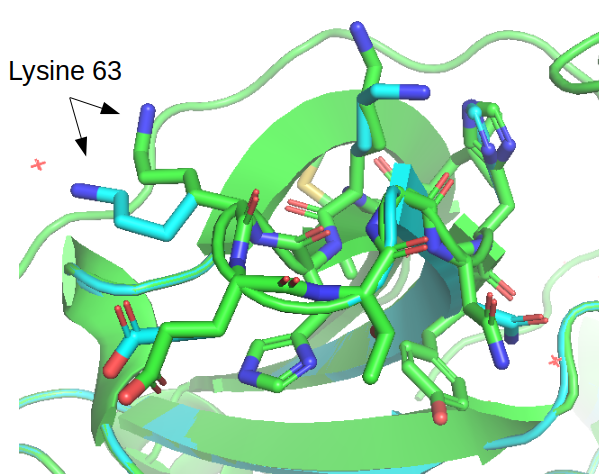

After running this the estimated stability of the protein 𝚫G went from +82.95 kcal/mol to –55.43 kcal/mol. There is a detailed description of the many small changes that led to the very large difference in predicted stability. The repaired structure is outputted in the same folder and the figure below illustrates a few cases where the conformations of the side changes were moved between the original structure and the repaired structure.

You can retrieve the repaired PDB to your local computer via the export function in Rstudio or using the scp command:

scp <user>@cousteau.ethz.ch:./foldxtest/5J5X_Repair.pdb ./

Generating mutated structures and estimating the impact on the stability can be done using the BuildModel command. It requires a text file holding a list of mutations to test with each mutation in a line in the format such as “LA224A;” corresponding to starting amino acid (L), the chain (A), the position (224) and the amino acid we want to mutate it to (A). As an example we can attempt to predict the impact of mutations in two positions, L at position 224 that is part of the core of the protein and I at position 339 that is at the surface. In R studio workbench we create a new text file and write in the following mutations:

LA224A;

LA224E;

LA224W;

IA339A;

IA339E;

IA339W;

Then save this file as “individual_list.txt” in the same foldxtest directory. Back in the terminal the prediction of the impact of mutations can be predicted using the following command:

foldx --command=BuildModel --pdb=5J5X_Repair.pdb --mutant-file=individual_list.txt

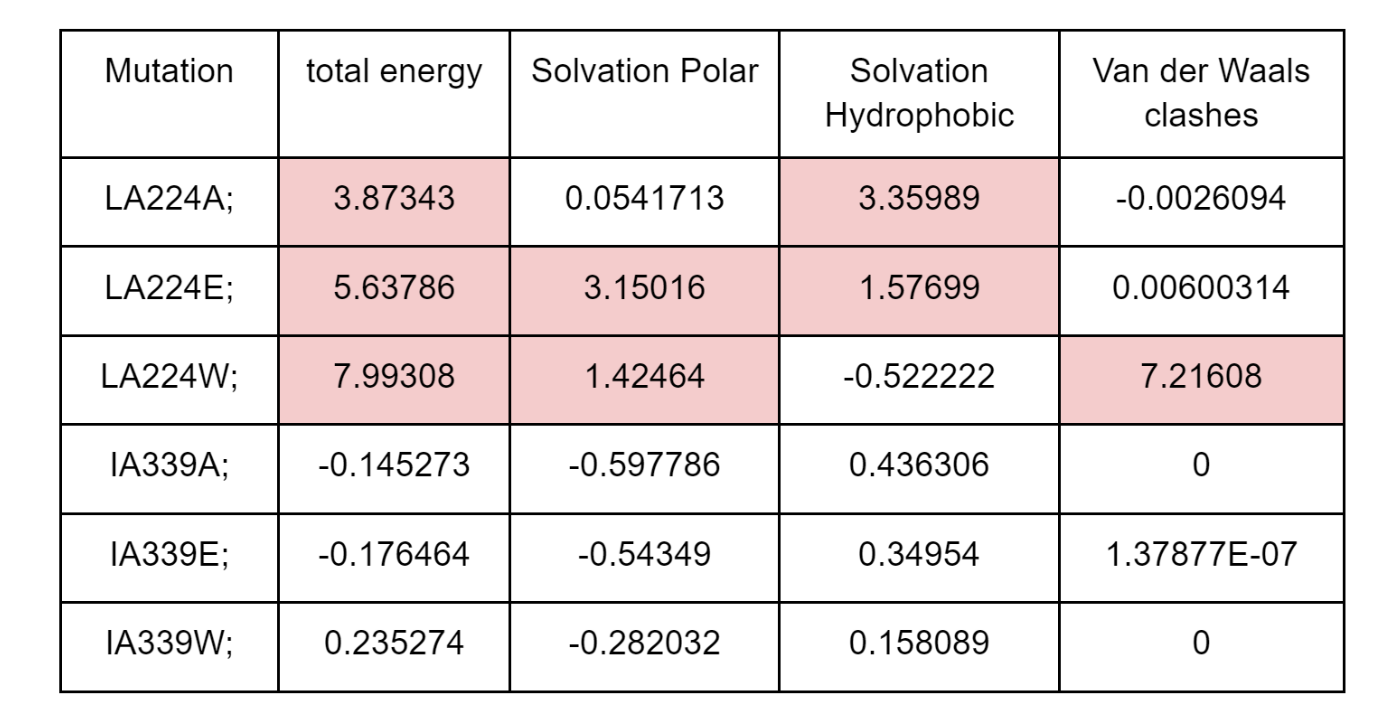

FoldX will generate an output PDB file with each of the mutated structures and the summary of predicted energy differences in “Dif_5j5x_Repair.fxout” which will have an entry per mutation in the same order as the list of mutations. The output contains information on the total 𝚫𝚫G as well as different components that contribute to the total score. As shown in the table below, the 3 mutations in the L224 core residue are predicted to be destabilizing with 𝚫𝚫G>2 kcal/mol. However, there are different reasons for the detrimental effect, with the mutation to the large tryptophan (W) causing a strong clash and the mutation to the small alaline (A) having a defect in solvation hydrophobicity, likely due to leaving a “hole” in the core of the structure. The mutation to the negative charge glutamate residue (E) causes issues with having hydrophilic charged residues in the core of the protein (solvation polar energy). The corresponding mutation in the surface residue I339 has essentially no predicted effect on protein stability.

In addition to BuildModel, FoldX can also perform a fast calculation of the impact of the mutation of every single residue to alanine. This can be achieved using the “AlaScan” command which is faster but less accurate than estimates obtained using the BuildModel command.

foldx --command=AlaScan --pdb=5J5X_Repair.pdb

The output of this command is a file “5j5x_Repair_AS.fxout” containing the predicted impact of mutating each residue to alanine in seperate lines. For example: GLY 9 to ALA energy change is 0.801459

Fold it¶

We are finished this week with Structural Bioinformatics and as such there is no homework for this week. Instead, you are encouraged to play the FoldIt g ame. This game teaches the gamer how to fold proteins in a visual way. It is also used for deriving actual protein structure predict ions by aggregating the accumulated experience of the best folders. For example, FoldIt players have successfully predicted the structure of an HIV protei n and have been acknowledged for this in the author list of the paper.